Researchers with Johns Hopkins Medicine and computer scientists from Johns Hopkins University’s Whiting School of Engineering are analyzing thousands of abdominal scans in an effort to catch pancreatic tumors while they are still operable. Another computer scientist developed an algorithm used at Johns Hopkins hospitals to help diagnosis sepsis before it becomes fatal.

Yet as artificial intelligence – and digital health in general – become more common in health care, the words of Johns Hopkins Hospital founder William Osler carry more weight, according to Daniel Ford, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research and a professor of medicine.

Osler said, “‘Listen to your patient. He’s telling you the diagnosis,’” Ford said in remarks opening the Johns Hopkins Research Symposium on Engineering in Healthcare. ”Clinicians have had prediction tools available for decades. But even with decision support tools, we have not always improved patient outcomes.”

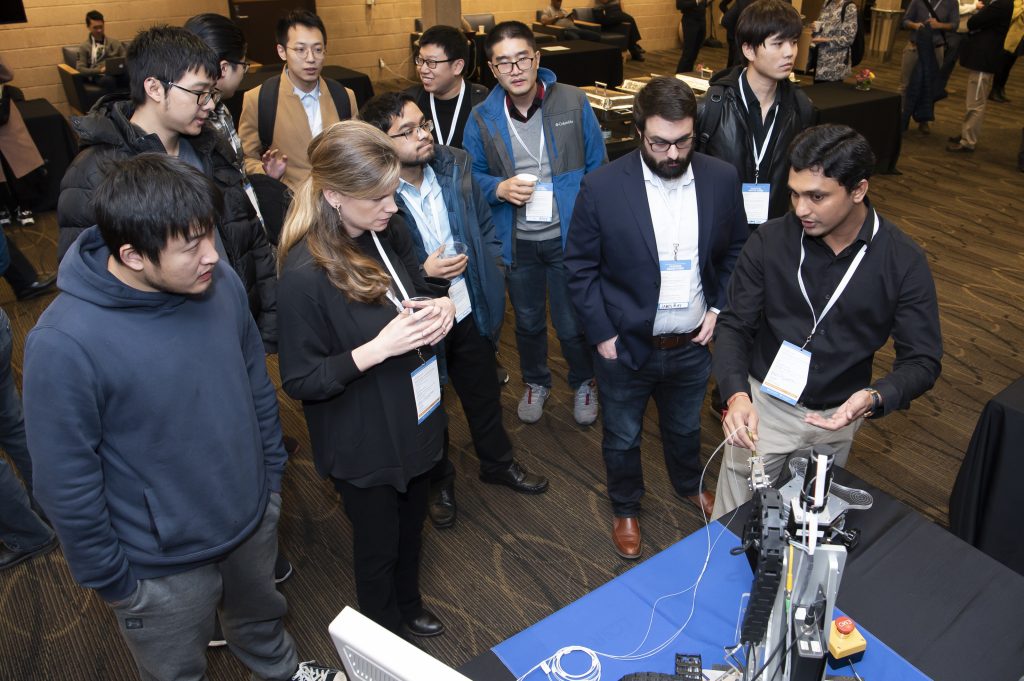

More than 250 researchers, clinicians and students from Johns Hopkins and around the country came to Turner Auditorium recently to attend “AI in Healthcare: From Bench to Bedside, an all-day symposium hosted by Johns Hopkins’ Malone Center for Engineering in Healthcare and the Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Ford acknowledged AI will be an “integral part of the future of medicine,” noting an estimated $6.6 billion will be spent on health care AI by 2021 and that analysts at the consulting firm Accenture estimate the technology will save $150 billion in annual health care by 2026.

Ed Schlesinger, dean of the Whiting School of Engineering, said the amount of data available, plus advancements in quantitative and qualitative tools, mean today’s health care industry is more likely to benefit from using AI that at any other time in history. But he agreed with Ford that the technology must serve the patient first.

“True progress will only result from the collaboration that’s aimed at solving real clinical problems,” he said.

Improving Efficiency

Keynote speaker Maryellen Giger, a University of Chicago radiologist who has worked for decades on computer-aided diagnosis and machine learning, said computers in her field are improving efficiency by shifting from being the second readers of scans to reading them in concert with a radiologist.

“The bulk of time that a radiologist spends is not in interpreting the image. It’s in the setup that it takes,” she said. “And that’s where AI will help.”

Keynote speaker Maryellen Giger

As part of its inHealth precision medicine initiative, Johns Hopkins has spent $600 million since 2010 updating its electronic health records, data from which is uploaded into its cloud every night, said Scott Zeger, co-director of Johns Hopkins InHealth and the John C. Malone Professor of Biostatistics at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The institution’s more than 300 data scientists, many located at one of 17 precision medicine Centers of Excellence, can use the information to assess a patient’s condition and project the benefits and risks of future treatment options.

Others speakers noted using AI in health care could mean finding ways to work more efficiently. A team with Sinai BioDesign at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York worked with clinicians to develop a faster way to interpret imaging by redesigning the work order for patients having an acute neurological event, such as a stroke. This improvement cut down response time by 12 minutes, “which could mean life or death,” said Anthony Costa, director of Sinai BioDesign.

The Center for Artificial Intelligence in Diagnostic Medicine at the University of California, Irvine created an AI “sandbox” where doctors and researchers can create their own tools as well as use elements developed by others, according to co-director Peter Chang. Almost all of the projects have originated in ideas from the university’s health system, he added.

“Our job is to streamline and remove bottlenecks so tools can be used in clinical practices,” he said.

Yet Chang and other speakers reiterated that all of the AI technology available will not cure any patient unless physicians use it.

“Close collaboration with engineering allows us to make cutting-edge advances,” said Ford. “But it’s also crucial to remember all of these advances are there to help the clinician.”

This article originally appeared in DOME JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2020